- MathNotebook

- MathConcepts

- StudyMath

- Geometry

- Logic

- Bott periodicity

- CategoryTheory

- FieldWithOneElement

- MathDiscovery

- Math Connections

Epistemology

- m a t h 4 w i s d o m - g m a i l

- +370 607 27 665

- My work is in the Public Domain for all to share freely.

- 读物 书 影片 维基百科

Introduction E9F5FC

Questions FFFFC0

Software

Andrius Kulikauskas gave this presentation in Lithuanian (Kūrybos prasmė ir meno taisyklės) on 22.03.2014 at the conference "Connections of Psychology of Art with Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art".

Does art have rules? Does art have a purpose? What do you think?

In 2014, I presented my thoughts in Lithuanian at the Lithuanian Cultural Institute. Ten years later, I present this to you translated into English. You will see how this fits with the videos I have been making about the meaning of life.

I am Andrius Kulikauskas. This Math 4 Wisdom.

Purposes of Art. Rules for Art.

I am a self-taught thinker as well as a self-taught artist. As a child, I wanted to know everything and apply that knowledge usefully. Truth be told, no one is interested in my conceptual abstractions. But when I depict them in an art exhibition, people are happy to listen to my thoughts not just for five minutes, but for a whole half hour.

I will present to you the connections that I perceive between the meaning of creative work and the rules for making art. These are also the connections between the philosophy of art, which explores the meaning of creative work, and the psychology of art, which explains the rules for art, how it works upon us and through us. I will first give personal, practical examples to present the meaning of creative work and the rules for art, and then I will define concepts abstractly and relate them to each other.

What is the meaning of creative work? In the village of Eičiūnai, I live in a house which I have dedicated to my own creative work and that of my neighbors. Twenty-year-old Povilas Koruža created a video here, in which he raps sincerely what the loss of his parents means to him, an orphan:

I envy all of you who still have parents, who see their eyes and hear their voices. They love you and I know it well. So act decently, as you will lack them. For I can only go to the cemetery, silently pray or light a candle.

After hearing this recording, I hastened to write to my father, brother, sister. This is impactful creativity. Povilas's sister, Aistė Kaminskaitė, says that three years ago, he couldn't find anything to do, but now he is busy creating! I think this is the meaning of creative work, discovering what to do with one's freedom, and at the same time, discovering why to do it. In life, we often lose sight of why. In beauty, we perceive that there is a reason why. With creative work we realize, learn to master, bring to life that reason why.

What to do with myself? I wish to establish a culture of independent thinkers. I want to know fundamentally, discover true concepts, communicate with all by way of them, that together we learn forever, grow forever, live forever, here and now. I seek knowledge, how to inspire myself and others with creative work, how to move us to action. I seek rules for impactful creative work. Thus I engage my artist friends, sculptor Algirdas Zokaitis, stained glass artist Albinas Markevičius, director Rimas Morkūnas and my brother, artist Jonas Kulikauskas.

Zokaitis keeps telling me, "There are no rules for art." But I collected a bunch of rules that I follow:

- Don't use an eraser. Don't make mistakes.

- Don't lift up the pencil. Draw long, bold lines.

- Make the colors bright. Avoid brown and gray.

- Evoke feelings. Draw faces, postures, bodily arrangements.

- Step inside the person you are drawing. What is it that reveals them?

- Express the deepest truth. Beauty emerges of itself.

- Make everything significant. Give meaning to all colors, all directions.

- Make the most of possibilities. Create big and rough.

- Always create in new ways. Stay an amateur.

- Be vulnerable. Reveal yourself.

- Overdo it. Lean on your subconscious.

- Bring out the unexpected. Respect God's intervention!

My main rule is to express ever so boldly that which is most important to me and thereby distinguish my perspective from that of God's perspective, Why, which stretches beyond me. My unconscious opens itself to my sacred conscious, like a window to God.

In Chicago, I endeavored to convey with an art exhibition all of my thinking. This forced me to summarize it very simply. Life is the fact that God is good, but eternal life is understanding that God does not have to be good, life does not have to be fair. I pictured the good kid and the bad kid deal with that. In the final week, I worked for 33 hours without sleep. I was alarmed when, after two swift brush strokes, I saw a horned face, devilish, so foreign to me. Three-dimensional in way that I am not able to paint intentionally. I thought, what is God trying to tell me? And I realized that if the bad child is accompanied by the higher self, then he should likewise be accompanied by the lower self. Indeed, elsewhere in the bad child's world, I show hands that drag him down, but also hands that lift him up. Whereas there are no devils in the good child's world. These examples show how the rules of art and how creativity in general helps to leverage the unconscious and receive wise insights.

With these examples, I assert that the significance of creativity is to engage in it, to find something to do with one's freedom, for our free will is distinct from the circumstances of our fate and our creativity is not content with them. Through creativity and the resulting sensibility, we connect with a purpose higher than ourselves, for the sake of which we are, that is, with our creator, whose children we can be as co-creators. The rules of art teach us to express ourselves as boldly as possible, so that we can better distinguish between our own creation and God's creation, harmonize them, and create together.

I realize that my personal rules of art conflict with the aesthetics of the Chinese of the Tang Dynasty, (championed by professor Antanas Andrijauskas, organizer of this conference). I think this is because we have different goals. Now I will express with conceptual structures the universal human significance of creative work, the way in which, together with God, we develop an aesthetic sensitivity to his perspective, Why. Then I will present twelve circumstances by which we variously perceive that sense of aesthetic connection, that goal of creative work. Each and every goal of creative work is supported by a corresponding rule for art. I believe that these distinct rules are the principles of life formulated by architect Christopher Alexander and ground the pattern languages which he documents.

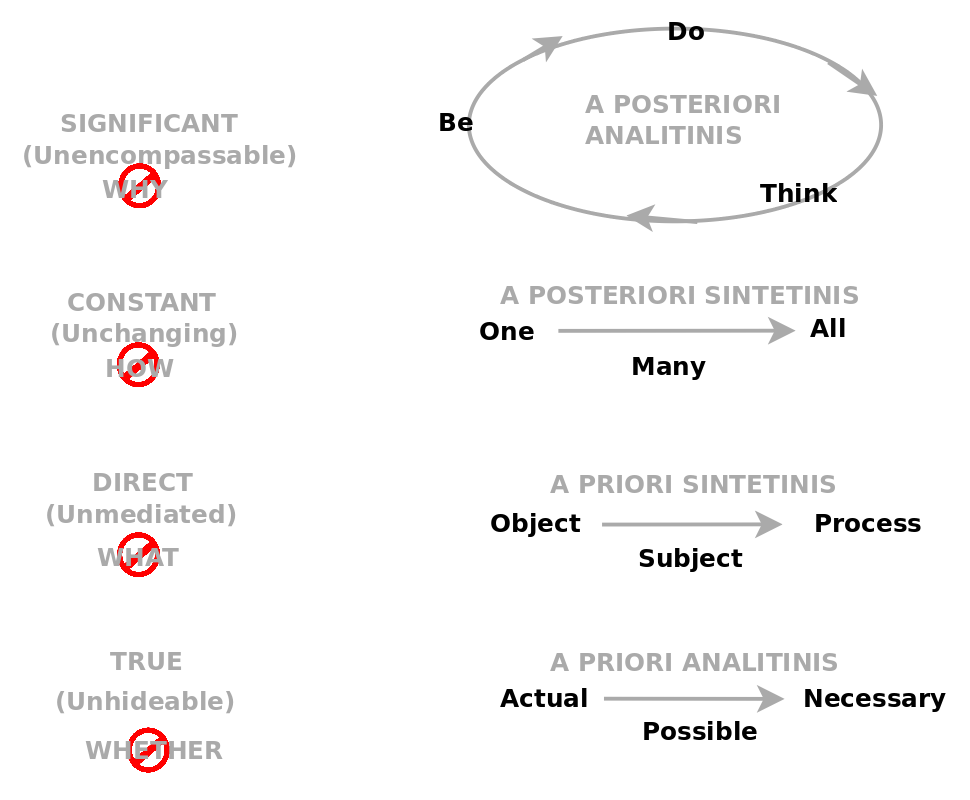

Amongst the ABC's of my philosophy are four levels of knowledge: Whether, What, How and Why. For example, we feel with our senses What is a cup. With our intellect we think How it is made and used. Alongside these practical, every day, human levels, we can contemplate Whether there would be a cup if nobody saw it in the closet. And if we knew Why there is a cup, then we would know everything related to it, including us and God himself. There are also three states of participation: being, doing, thinking. In an endless cycle, we take a stand, follow through, reflect and so we live.

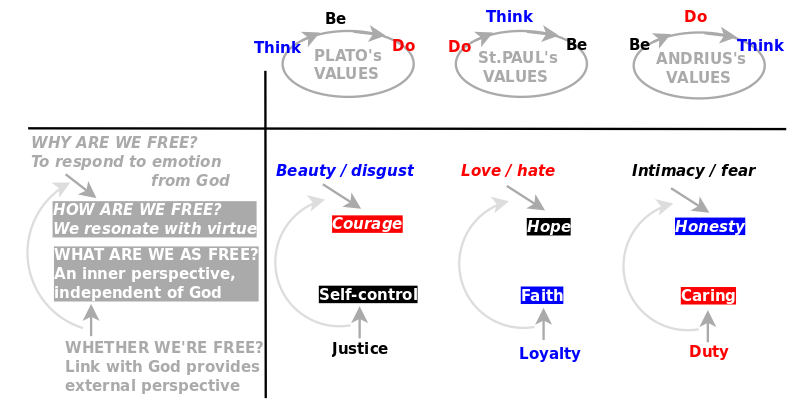

I noticed that the values of Plato's Republic are a combination of this foursome of knowledge and threesome of participation. Similarly, St. Paul's values are their permutation, that is, their rotation along the cycle of participation. Accordingly, we can derive a third set of values. These three sets of values define the meaning of life, how God makes our efforts meaningful.

Plato's Republic is just and its people have self-control. Justice is an external perspective, whereas self-control is internalized as an internal perspective. Similarly, we internalize external loyalty as internal faith. We internalize external duty as internal caring. This is what a human can do. When a person has a relationship with God, then that person can think in terms of that God's external perspective. However, a person may not always have this connection with God, and then it is important that the person themselves, of their own internal perspective, obey, believe and care, thus recovering the connection with God and even expanding it. A person, internalizing their perspective, compose themselves, harmonize themselves, create themselves.

Such a person is like a musical instrument for God to play. A well-tuned person experiences wisdom as a feeling. She distinguishes what is beautiful and what is disgusting. Therefore, in my diagram, instead of wisdom, I write beauty and disgust. A person with self control will act like a warrior trained by Plato's wise man. She will resonate with courage, maybe even break norms, as ever beauty demands. This fleeting moment of beauty is immortalized as the virtue of courage, which becomes part of her character, her habits, her soul's dowry. This is how God makes meaningful what a person internalizes. God plucks the strings a person tunes.

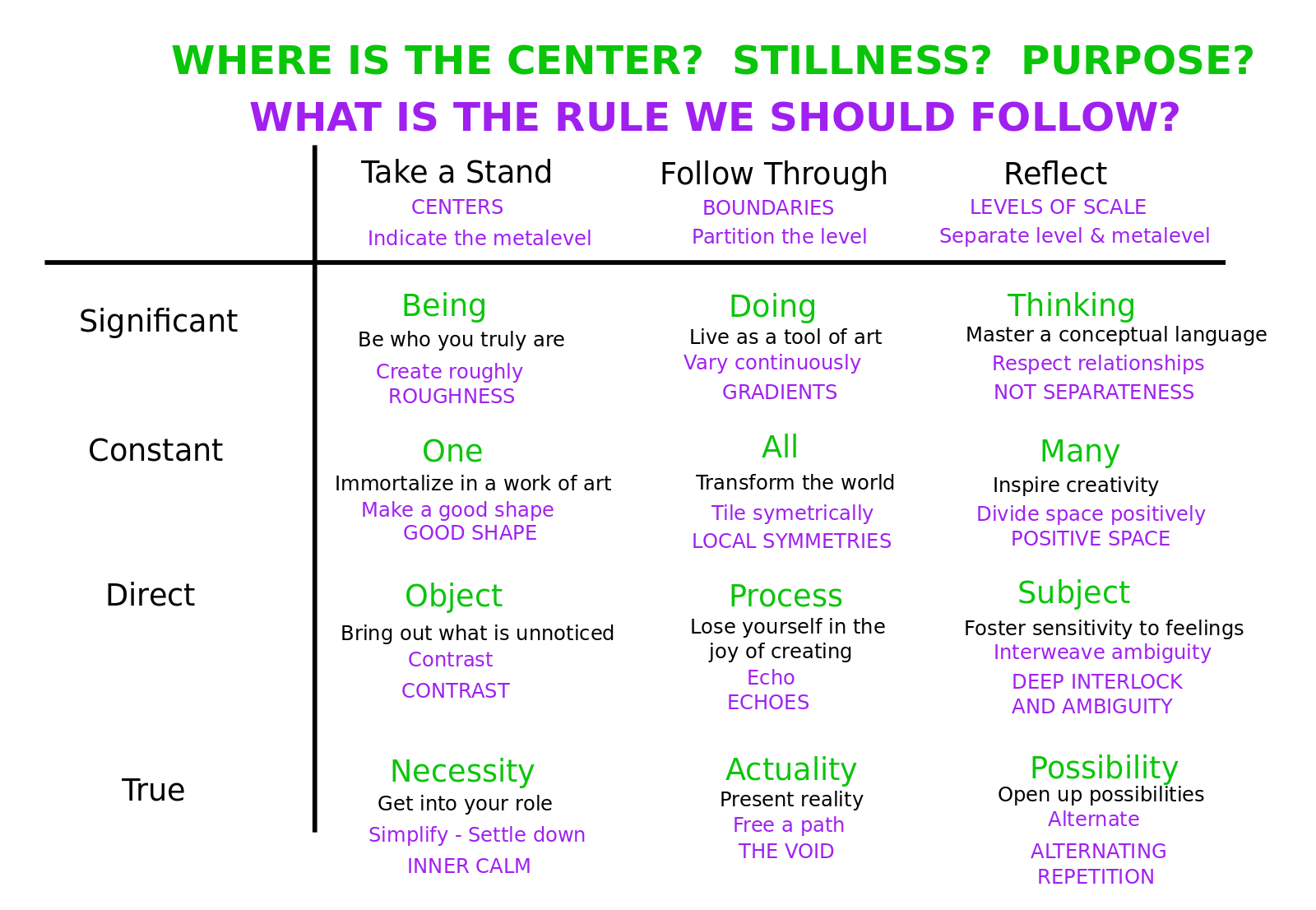

This connection between God and human is completely free. For by internalizing God's external perspective, a person grows independent of God, and yet it is precisely God who grows them. This is not a knowledge that separates us from God, but rather a sensibility that unites us with God, to the why beyond us. We imagine in many different ways that Why, that purpose, that sensitivity in our earthly circumstances. Robert Genn collected about one hundred quotes of artist, how they imagine the purpose of art. I systematized them according to the circumstances of the imagination, in which that purpose is to be found. For example, one purpose is to immortalize something in an art work. Another purpose is to inspire others. A third purpose is to remake the world. The first purpose lies in the One, the second in the Many, and the third in All. Thus emerges what Kant would call the twelve categories.

I paired each purpose with the rule of art which highlights it. These rules are architect Christopher Alexander's principles of life. I think he is the greatest thinker of our time, little known in Lithuania but well known in Silicon Valley and the network society. In 1979, with his books The Timeless Way of Building and A Pattern Language, he investigated why traditional houses, built by amateurs, are cozy and refreshing, whereas modern buildings, designed by professionals, make one feel dead.

Christopher Alexander noticed that, in our time, buildings are designed in minute detail and then plopped down without regard to their surroundings. Whereas, in ancient times, buildings were constructed by applying patterns, that is, according to rules of thumb and optimized on site. For example, it is desirable that every room be illuminated by windows on two sides, so that the light does not come in sharply from one side, as in this hall. They would start on site with the biggest questions, where to build the house, how to face it, how to lay it out, and then they would decide on ever smaller matters, those that came up unexpectedly along the way, ever relying on intuition, so that one would feel better, cozier, more whole, healthier, freer...

Patterns relate activity and structure. Recurring activity evokes spatial structure, and structure determines the possibilities of activity. For example, I can wash the dishes once, as ever I like, but if I wash them every day, then the clean water will appear above, the dirty water will fall below, the soap will be within reach, and so on.

Personal rules in making art are such "patterns", such rules of thumb. They combine the activity of the creator and the structure of creations, just as self-control accords with justice. We apply our rules locally with sensitivity. Therefore our rules have to be quite flexible to ever more vividly capture and maintain our sense of beauty. They then embolden us to create ever more boldly. This is how we create our eternal life and partake in it.

Christopher Alexander has described 250 such patterns which he personally applies in his architecture, from a neighborhood block to a single windowsill. In 2004, in his four volumes, "The Nature of Order", he put forward fifteen principles giving life to creative work. The three most important principles are: strong centers, clear boundaries, levels of scale. I present the remaining twelve laws in the table as rules for making art that support the creator's purposes. For example, if you seek to immortalize yourself in a work, then create a good shape; if you wish to inspire others, make positive space; if you're going to remake the world, then lay down a foundation with local symmetry.

The psychology of art could examine whether such rules work and whether they can be refined. I myself will speak of twelve circumstances in which we see the purpose of creation. Kant would call them categories, but I understand them as the backdrops of our imagination, the worlds, topologies, circumstances that it supplies. Kant believed that they derive from the form of a logical statement, but I derive them from mind games. The key to the game is sensibility, the negation of knowing. For example, the concept of "how" is negated by constancy, the lack of change. We can look for constancy. Either we find One example of constancy, or we don't, in which case All is constantly unconstant. By this game, we define the concepts One and All, as well as a third concept, Many. After all, how do I know that what I select and what I examine are one and the same? Constancy is thus also in this regularity, which is to say, in the Many. We can now can imagine what it means for one's purpose to inhabit One or All or Many. The purpose is in the One when we immortalize ourselves in a work, it is in the All when we transform the world with symmetry, and it is in the Many when we inspire others by making positive space.

I think it is through such innate mind games that even a baby in the womb discovers the possibilities of its imagination. Kant himself thought that his categories would pave the way for future science. Perhaps we will achieve that it! How do the general rules of imagination, like the forces of nature, come together in life, and how do personal and cultural rules for art arise from them?

I will conclude by proposing a data-driven method to investigate these phenomena. I wrote a booklet in which I overviewed all my thinking. I illustrated it with more than three hundred pictures and photographs. These images meant one thing to me when I made them, and now they mean something else upon inclusion in my booklet. For example, I took a photo of my friend David Ellison-Bey, an independent thinker, with a flower. At the time, I saw him as gardening, which was one of perhaps two hundred activities in his Moorish Cultural Workshop. But now, in my booklet, with this photo, I am depicting the community of independent thinkers in general. Thus we see emerge the dimensions of semiotic ambiguity. One shoe can represent all shoes, a tool can represent a work or process, what is present - what is absent, what is certain - what is conditional. In expressing myself, I may evoke your response. The artist plays with such dimensions and attempts, sensitively, to capture them, to tinker with them successfully, to express, reveal and open them, as she or he is able.