- MathNotebook

- MathConcepts

- StudyMath

- Geometry

- Logic

- Bott periodicity

- CategoryTheory

- FieldWithOneElement

- MathDiscovery

- Math Connections

Epistemology

- m a t h 4 w i s d o m - g m a i l

- +370 607 27 665

- My work is in the Public Domain for all to share freely.

- 读物 书 影片 维基百科

Introduction E9F5FC

Questions FFFFC0

Software

Wroclaw Philosophers' Rally, July 6-8, 2017.

Determining Personal Responsibility for a Social Calamity

The Origins of the Holocaust in Lithuania

Five years ago, as a citizen, and a Lithuanian, in the course of an online discussion with Grant Gochin, a Lithuanian Jew in California, about the responsibility of Lithuanians for the Holocaust, I came to doubt what I thought I knew. I share with you a method that I developed for investigating personal responsibility for a social calamity, such as the murder in 1941 of practically all of the Jewish men, women and children in Lithuania's towns.

I wish to share a fundamental distinction between "having power" and "getting things done". One person may have power but not get anything done. Another person may have no power and yet get everything done. My analysis will show the degrees to which individuals are responsible for what gets done and what does not, whether good or bad. My goal, as a citizen, was to learn the extent of Lithuanian responsibility for the Holocaust. I consciously choose to be a Lithuanian, and so I should inquire whether there was or is something flawed or wicked in my chosen world view.

Often, it is supposed, that either some person with great power sets in motion a social calamity, or otherwise it is the unintentional product of happenstance or anonymous social forces. I develop an alternative view where a calamity can result from even a minor character's personal leadership, but depends on that individual's persistent learning, and thus must be purposefully intentional. A person must not simply stand in the right place at the right time, but must actively and willfully go and stay there to pull on the relevant system of levers.

My investigation focused on a question, Who wished for the death of all of Lithuania's Jews, including women and children? My focus allowed me to photograph and scan through 25,000 pages from more than 500 sources. In such a focused analysis, we must identify the core of the catastrophe. Lithuania's Jews were murdered by different perpetrators in a variety of actions. The most expansive were the more than 200 mass shootings of the inhabitants of the shtetls, the Jewish communities in Lithuania's cities, towns and villages.

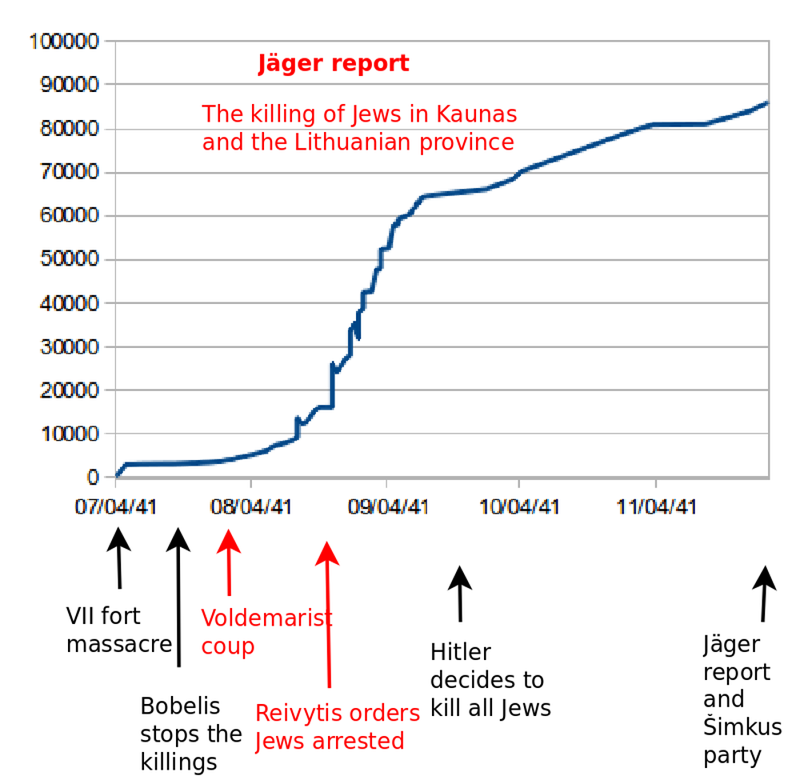

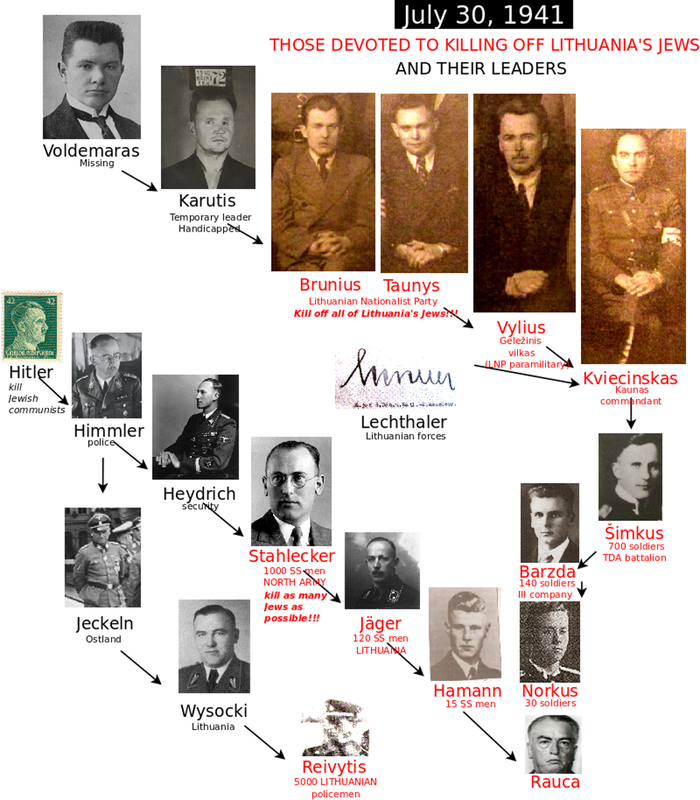

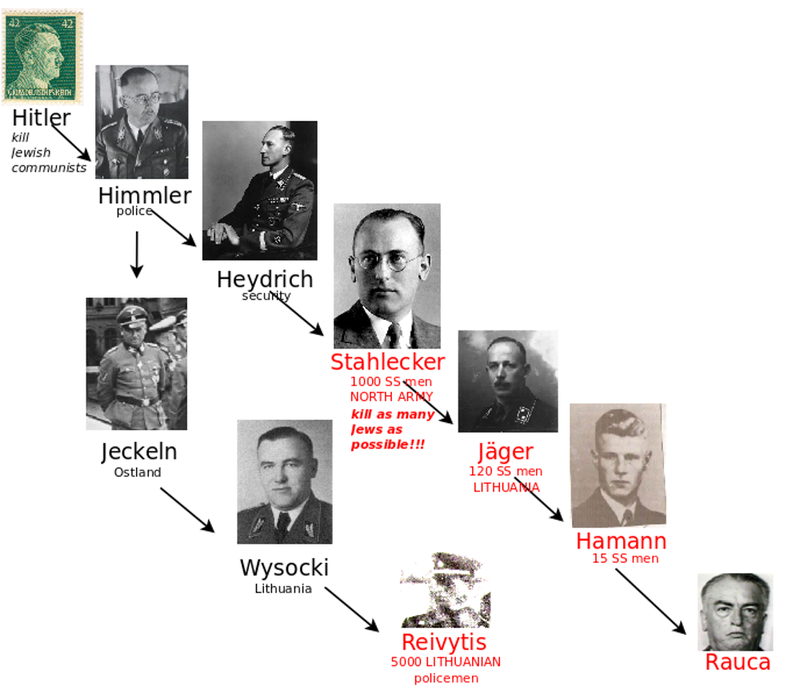

We analyze the timeline by which events proceeded. From the report compiled by Karl Jaeger, the leader of the SS in Lithuania, we can see how the Nazi invasion of the USSR on June 22, 1941, and the Lithuanian anti-Soviet uprising the next day, were quickly followed by the shooting of 3,000 Jews and Communists held at Kaunas VII fort on July 4 and 6. This was followed by a 3 week lull, after which hundreds and then thousands of Jews were killed every day.

We note when resources were assembled and how they were deployed. The killings were ordered by Karl Jaeger, who led only 120 SS men, including drivers and typists. This was clearly not enough to guarantee a genocide. But Jurgis Bobelis, the Kaunas military commandant who led Lithuania's 800 partisans, did not protest Jaeger's order, even though as an expert on military law he knew that it was a war crime. What is striking is that the killings were enthusiastically organized by Lithuanian officers, such as air force pilot Bronius Norkus, who at the start of the war happened to be on a weekend furlough from a Lithuanian unit in the Soviet army. The thousands of prisoners had been arrested by participants in the uprising led by the Lithuanian Activist Front. Perhaps even more heartless than the machine gunning of the crowds of men, without any pretense of trial, was the holding of women and children for days without water.

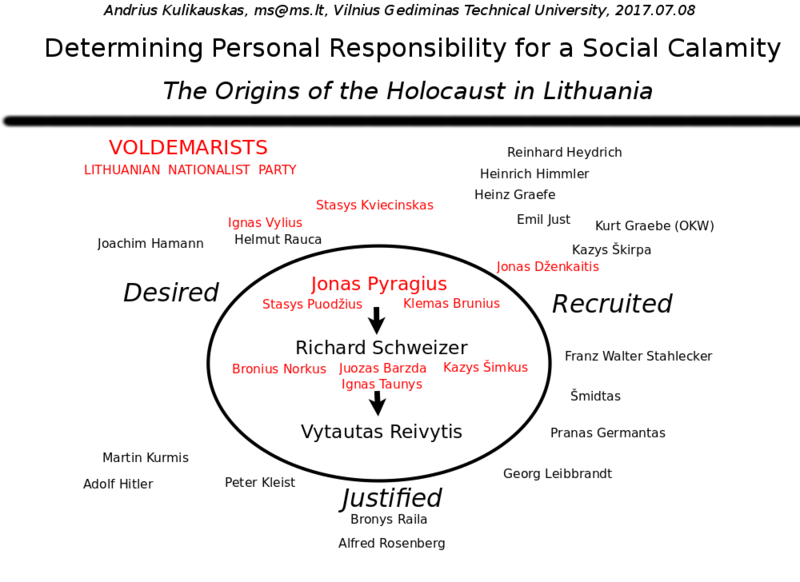

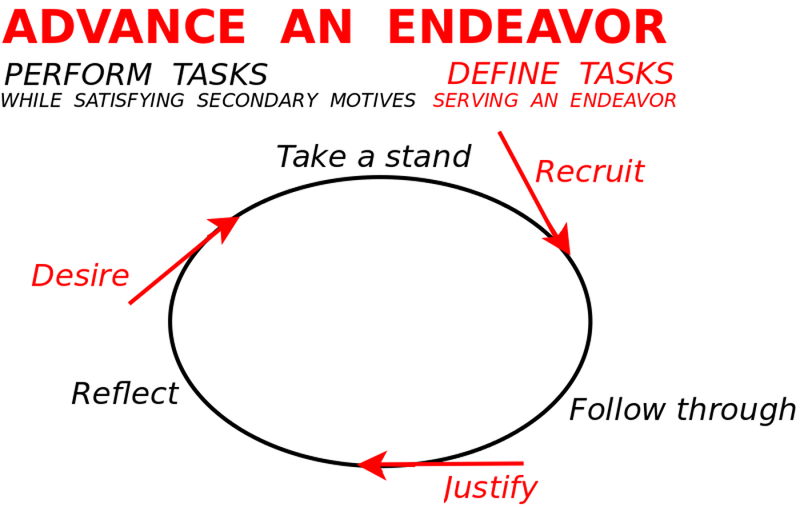

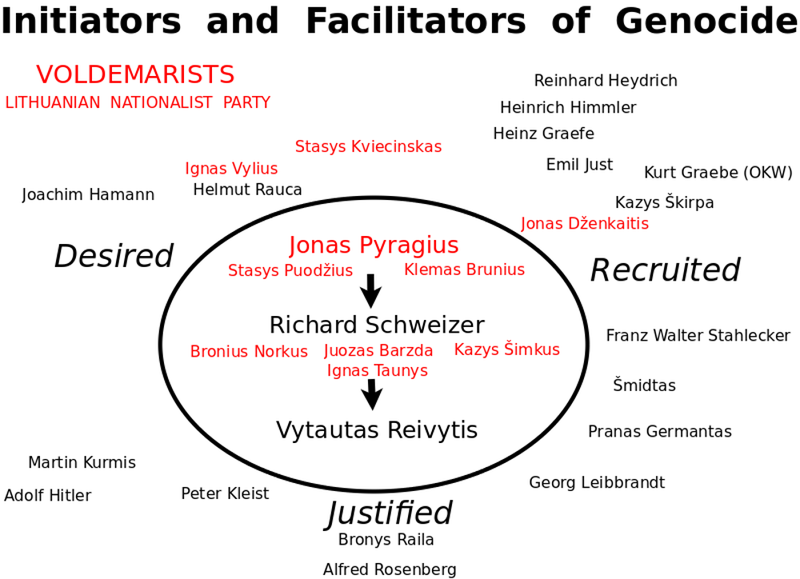

We can thus search among not only Germans, but also Lithuanians, who was it that championed such a calamity, and why? We look for self-driven people, idealists who were pursuing a personal vision, and thus able to psychologically prepare themselves as well as others. They are learners who develop themselves with an endless cycle of taking a stand, following through and reflecting. Primary responsibility for an endeavor, good or bad, goes to those who lead such a culture by insistently wishing, by recruiting participants, and by articulating justifications. The true champions are those who sacrifice their own needs and interests on behalf of their cause. Such dedication, continuity and consistency is essential so that the endeavor takes off and does not fall apart. But who would champion the murder of all Jews, women and children? We thus analyze the personal goals of those in the official chain of authority, especially as that changed over time, but also other individuals in their social networks.

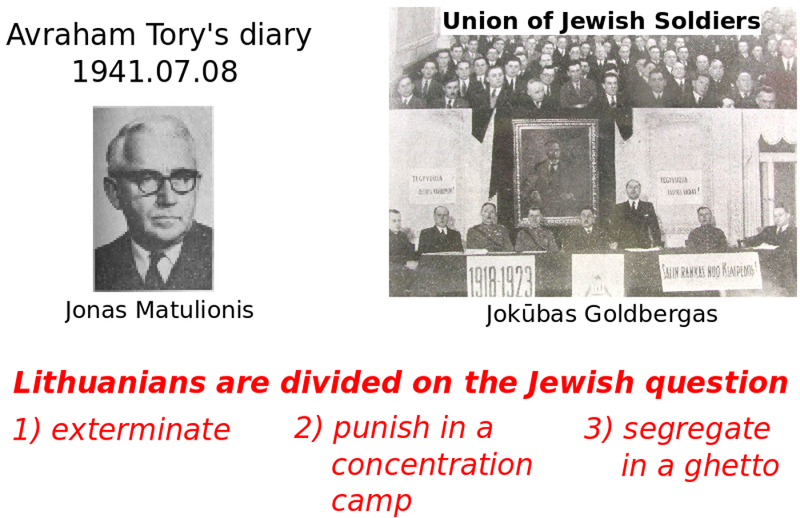

We note a spectrum of positions. While the massacre was happening, Lithuania's Jewishleaders approached Lithuanian leaders for help, for they had enjoyed good relations before the Soviet-occupation in 1940. Jonas Matulionis, the Finance Minister of Lithuania’s Provisional Government, explained to Jokūbas Goldbergas, the Chairman of the Board of the Union of Jewish Soldiers:

''The Lithuanians are divided on the Jewish question. There are three main views: according to the most extreme view all the Jews in Lithuania must be exterminated; a more moderate view demands setting up a concentration camp where Jews will atone with blood and sweat for their crimes against the Lithuanian people. As for the third view? I am a practicing Roman Catholic; I — and other believers like me — believe that no person may take the life of another person like himself. Only God may do this. I have never been against anybody, but during the period of Soviet rule I and my friends realized that we did not have a common path with the Jews and never will. In our view, the Lithuanians and the Jews must be separated from each other and the sooner the better. For this purpose, the Ghetto is essential. There you will be separated and no longer able to harm us. This is a Christian's position.''

The Christian position was similar to that of Archbishop Skvireckas and may be considered the baseline among Lithuanian leaders. Indeed, it was rather similar to that in place in Nazi-occupied Poland, which Heydrich's Einsatzgruppen had subjugated by killing 65,000 Polish intellectuals in 1939, and where Jews had been confined to ghettos near railway lines. And it was compatible with Nazi plans of deporting Jews to Madagascar, Lublin or Siberia. Who then championed the more extreme position of killing all of the Jews?

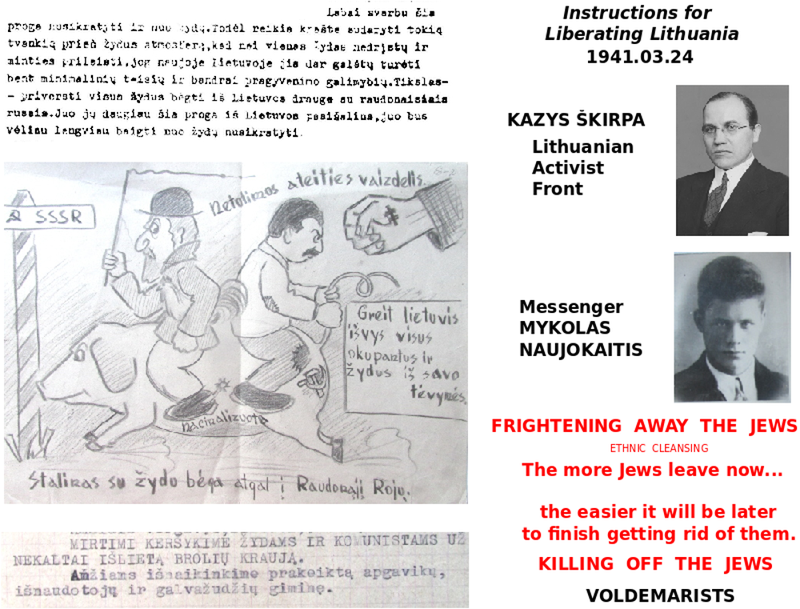

We can get evidence for the most extreme positions by relating them to the best documented positions, notably that of Kazys Škirpa, Lithuania's ambassador in Berlin, who protested the Soviet-occupation and led the anti-Soviet uprising. We have his 260 page memoir, which he wrote during the war, along with 110 documents he assembled, including 20 which advocated driving out Lithuania's Jews as part of the uprising. He was not personally antisemitic, but he understood that there could be no place for Jews in a New Lithuania if it was to be part of Hitler's New Europe. He reasoned that Lithuanians hadn't stood up to the Soviets or to Lithuanian Communists, but he might well incite them to fight Jews. In July, 1940, he started two myths which thrive to this day: first, that Jews had wronged Lithuanians, and second, that if Lithuanians wrongedJews, then it was simply revenge. These myths grew popular as Lithuanians grew ashamed of themselves for having accepted Soviet occupation and annexation.

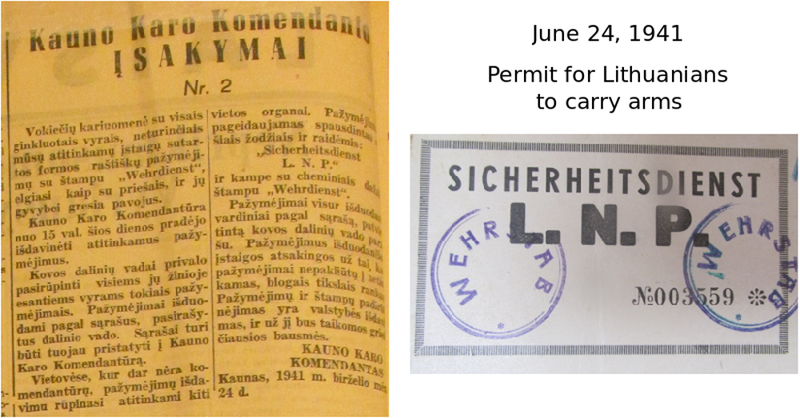

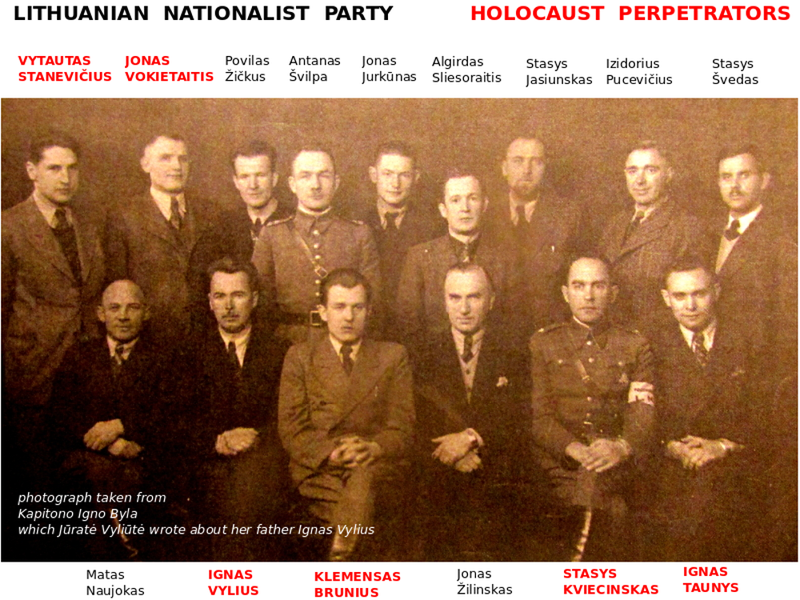

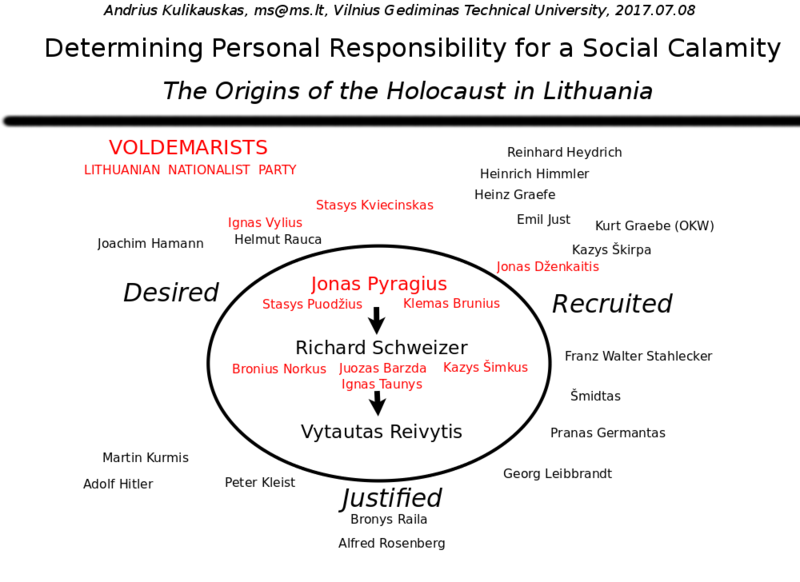

However, Škirpa's positions turned out to be unrealistic for Lithuania's fascists, the Voldemarists, who Škirpa relied upon. Škirpa was insistent on declaring Lithuania's independence even against the wishes of the Nazis. The first priority of the Voldemarists was to be on best terms with the Nazis and therefore they secretly betrayed Skirpa and founded the Lithuanian Nationalist Party, whose letters LNP appear along with the notorious Sicherheitsdienst on the permission slips which the Germany army issued for Lithuanians to bear arms. And the classes which they recruited Lithuanians for in Prussia included instructions on how to sneak into Soviet-occupied Lithuania and prepare activists there to organize the killing of all Jews. One week before the invasion, the draft program for the LNP included the goal of deleting Jews from life. The Voldemarists hoped that by killing Lithuania's Jews they would prove that Lithuanians are Aryans, worthy of bearing arms, and at the end of the war, Hitler would grant Lithuania independence.

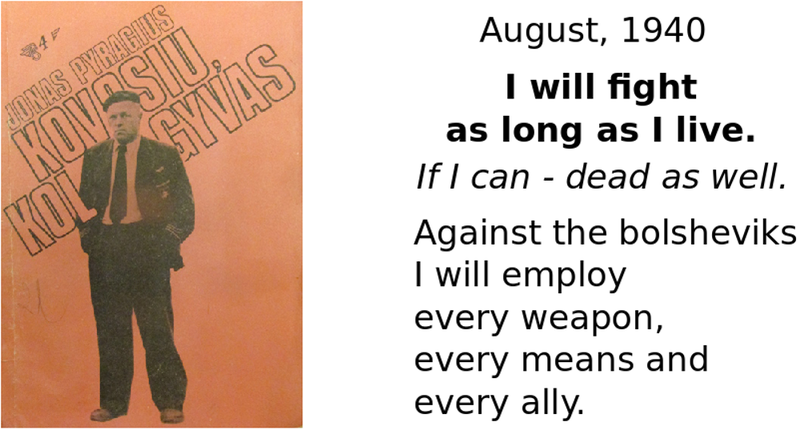

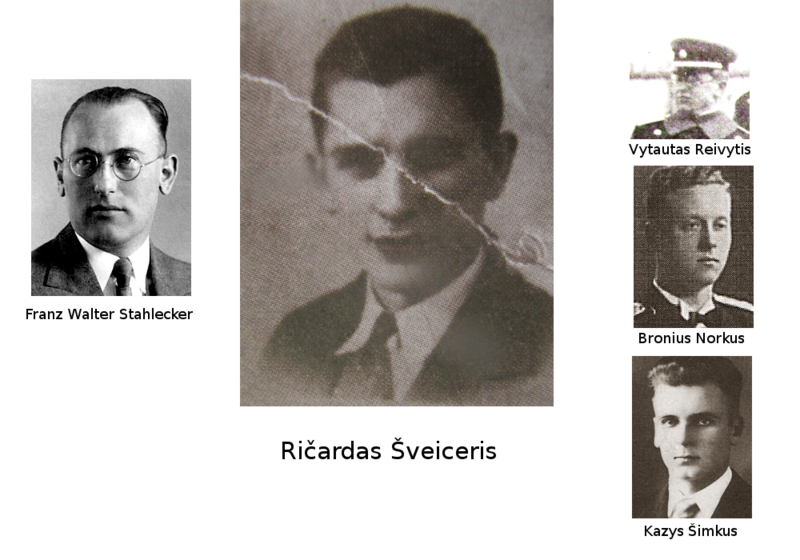

Who among them was the champion of genocide? We can analyze social networks to determine who belonged to the Voldemarists and what relations they had with Germans and Lithuanians at different positions in the spectrum of malice. We can discern their personal goals from their interactions with others. Zenonas Blynas was the leading intellectual of the LNP. His diary details his dispute with air force pilot Jonas Pyragius about the Holocaust. Blynas thought that Lithuanians had killed so many Jews that Lithuanians had a right to demand a promise of independence. He also complained that the Germans only filmed Lithuanians as killers and never themselves, which made the killing seem dishonorable. Pyragius argued that killing Jews was an end in itself and thereby revealed himself as a true champion.

What sets Pyragius apart is his willingness to risk his life for the sake of killing off Lithuania's Jews. The Voldemarists were caught off guard when students in Kaunas declared Lithuania's independence and established a Provisional Government. On the night of July 23, 1941, Pyragius led the Voldemarists in a coup, which was purportedly against this Provisional Government, but was truly against the commandant, Bobelis,because after the massacre at Kaunas's VIIth Fort, he had stopped the killing of Jews, and because he and mayor Palčiauskas had delayed the Jewish ghetto by an entire month. We know that the Voldemarists acted of their own initiative because afterwards Jager chastised them that, if they ever did anything like that again, their heads would roll. Indeed, there is a document from the day before the coup where the German commandant von Pohl orders Bobelis not to allow any cleansing operations without his permission. From the document it is clear that its purpose was to help Bobelis keep the Voldemarists in line, for if any Germans had been urging them on, von Pohl would have addressed such Germans directly. After the coup we see that the killing of Jews proceeded in the hundreds per day, and then thousands.

Another champion of genocide was Vytautas Reivytis, the leader of Lithuania's security police who the Voldemarists installed after their coup. Reivytis led Lithuania's 5,000 police officers in the arrest of some 100,000 Lithuanian Jews, which is much harder than killing them. His orders issued on August 16, 1941 were in the name of Lithuania's police, which is to say, in the name of Lithuania, and on behalf of Lithuania. If they had been in the name of Nazi Germany, then some of Lithuania's police might have taken action to help Jews flee.

A third champion of genocide was the German Lithuanian double agent Ričardas Šveiceris. He spent the year before the war in the border town of Eitkūnai, where he worked for the SD and where his acquaintance, Reivytis, worked for German military intelligence, Abwehr. Šveiceris then attended the Einsatzgruppen training school in Pretzsch, where he became translator for Franz Walter Stahlecker, who led Einsatzgruppe A, which traveled through Lithuania on the way to Leningrad. Šveiceris introduced Stahlecker to the Voldemarists, Norkus and Šimkus, and accompanied Stahlecker in his unsuccessful effort to convince police chief Dainauskas to organize pogroms. Flicking his finger against his head, Šveiceris showed Dainauskas what was going to happen to the Jews. We thus see Šveiceris's key role as a networker in Lithuania, how he must have opened Stahlecker's eyes to the possibilities. Šveiceris also was present at the celebration which the Lithuanians held for Jaeger on November 29 when he finished killing Lithuania's Jews.

Pyragius, Šveiceris and Reivytis are three relatively minor characters who weren't convicted by any court of law, and may not be convictable by such a standard. Nevertheless, by this historical analysis, they reveal themselves as dedicated perpetrators of the genocide of men, women and children. As such, they were possibly more directly responsible than more famous and powerful Nazi German leaders.

Karl Jaeger was officially responsible for the Holocaust in Lithuania. But he learned that he would be killing Jews just a few day before the invasion; he did not show particular initiative or innovation; and he was remorseful after it was all over. He was just doing his job. Whereas in the first week of the war, his boss Stahlecker launched three pilot projects for killing Lithuania's Jews. He ordered Bohme to kill them along the border with Prussia, he assigned Hamann to lead a notorious killing squad of fifteen SS men, and with Šveiceris's help, he inspired Voldemarists and other Lithuanians to conduct pogroms. However, ultimately, Stahlecker was more interested in fighting partisans than murdering Jews. Evidently, he advanced his career by killing as many Jews as he could, but he wasn't personally intent on killing all of them.

It may be that Stahlecker's dynamic efforts and the Voldemarists' enthusiasm at Kaunas's VII-th fort inspired Nazi Germany's leadership to expand its objectives. In March, 1941, Hitler had warned his generals that they would not abide the rules of war upon invading the Soviet Union, but would kill, without trial, all Communist commissars and Communist Jews. Upon entering any city, the Einsatzgruppen were expected to massacre Jews, if possible, by allowing or inspiring local pogroms. On July 4, Blume was reprimanded for not doing so. Even so, massacring hundreds of Jews was less than killing all of them. Judging from conversations between German and Jewish leaders in Kaunas, the purpose seems to have been to give Jews prompt reason to locate into ghettos so that they would be safe from the locals, and in the hands of the Germans. Also, Hitler emphasized punishing Jews for their misdeeds, in a word, Bolshevism, and pogroms by locals expressed with terror what Germans could execute by right.

Himmler's personal dream was to lead Germanic warrior farmers in colonizing the lands East of Russia, a process that might take decades to displace thirty million Slavs. He thought in terms of deportation rather than annihilation. But on July 8, two days after the Kaunas massacre, he seems to be competing with Stahlecker. Himmler came to Bialystok and was disappointed with the low death count - 700 Jews burned alive in a synagogue - and ordered more killed - another 1,000 were. He met with Hitler, who used the Soviet order for partisan warfare as an excuse to exterminate anyone hostile. Within a week, Himmler ordered 11 battalions of Order Police to join the laggard Einsatzgruppen in Russia Central and Russia North, and he brought in the genocidal Jeckeln, who innovated sardine pack killings. Himmler also appointed Globocnik, a champion of genocide, to pursue his visions of settling warrior farmers. And yet Himmler's genocidal actions seem primarily motivated at currying favor with Hitler. Hitler is certainly responsible for the overall tragedy of World War II and the Holocaust. Yet, personally, he seems to have devoted his creative energies to military planning, resettling Crimea, and architectural fantasies, rather than tormenting Jews. He did believe in "the intoxication of murder" and he was a champion of murderous eugenics. But, pragmatically, in his racial caste system, it was useful to have Jews, because everybody needed somebody to look down on and somebody to look up to. He did take credit for killing the Jews of Nazi-occupied Europe, and even prophesying that, but central to his vision was hating and punishing them and eliminating them from Europe. Lithuania's champions of genocide may have opened up the possibility of killing them all, which then became a necessity, if Hitler was to be the most ruthless of all.

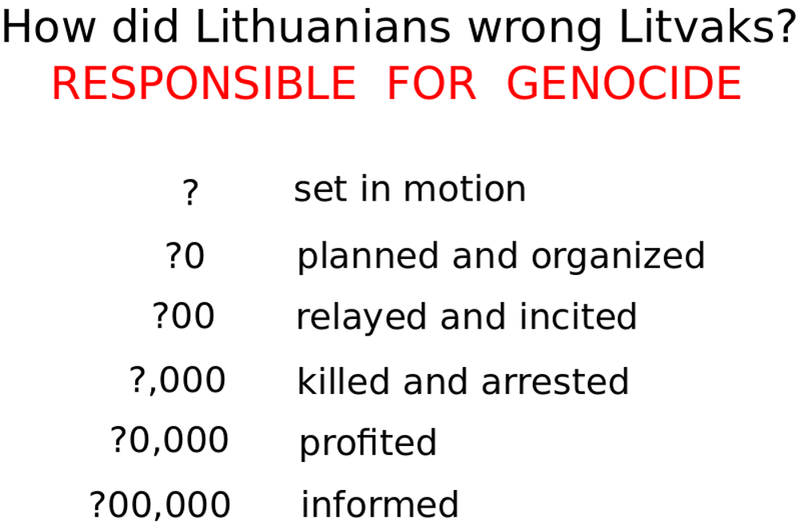

Primary responsibility for a social calamity can be assigned to the champions who pull it together by wishing, recruiting and justifying. Secondary responsibility can be assigned to those opportunists who support some part of that learning cycle. They are not sacrificing themselves for a cause, but rather participating for ulterior motives, such as advancing their careers, satisfying perverse pleasures or personally profiting. Certainly they participate voluntarily, for it is not possible to force one to exercise creativity, as in organizing others. In Lithuania, the handful of champions were supported by a pyramid of such opportunists, with dozens of organizers, hundreds of messengers, thousands of killers, tens of thousands who appropriated Jewish property or bought or sold it, and hundreds of thousands who snitched on neighbors who might be hiding Jews. Finally, ternary responsibility can be assigned to those who, like slaves, are forced to commit crimes. Even slaves get resources to sustain themselves. And so even slaves can choose to share some resources or show good will.

In studying the origins of the Holocaust in Lithuania, we have shown how to consider personal responsibility for such a social calamity. We can likewise investigate today who is personally creating our financial, environmental and political crises.